Now that we know what a perineal tearing can look like, let’s dive a little deeper into the WHY they happen. Let’s be realistic, I don’t know anyone that wants a perineal tear and often times it’s presented as a doom and gloom situation. So we’re going to look at two things - first, what may increase our risk to have a tear and then what we can do to minimize that risk!

What do we know about why perineal tears happen?

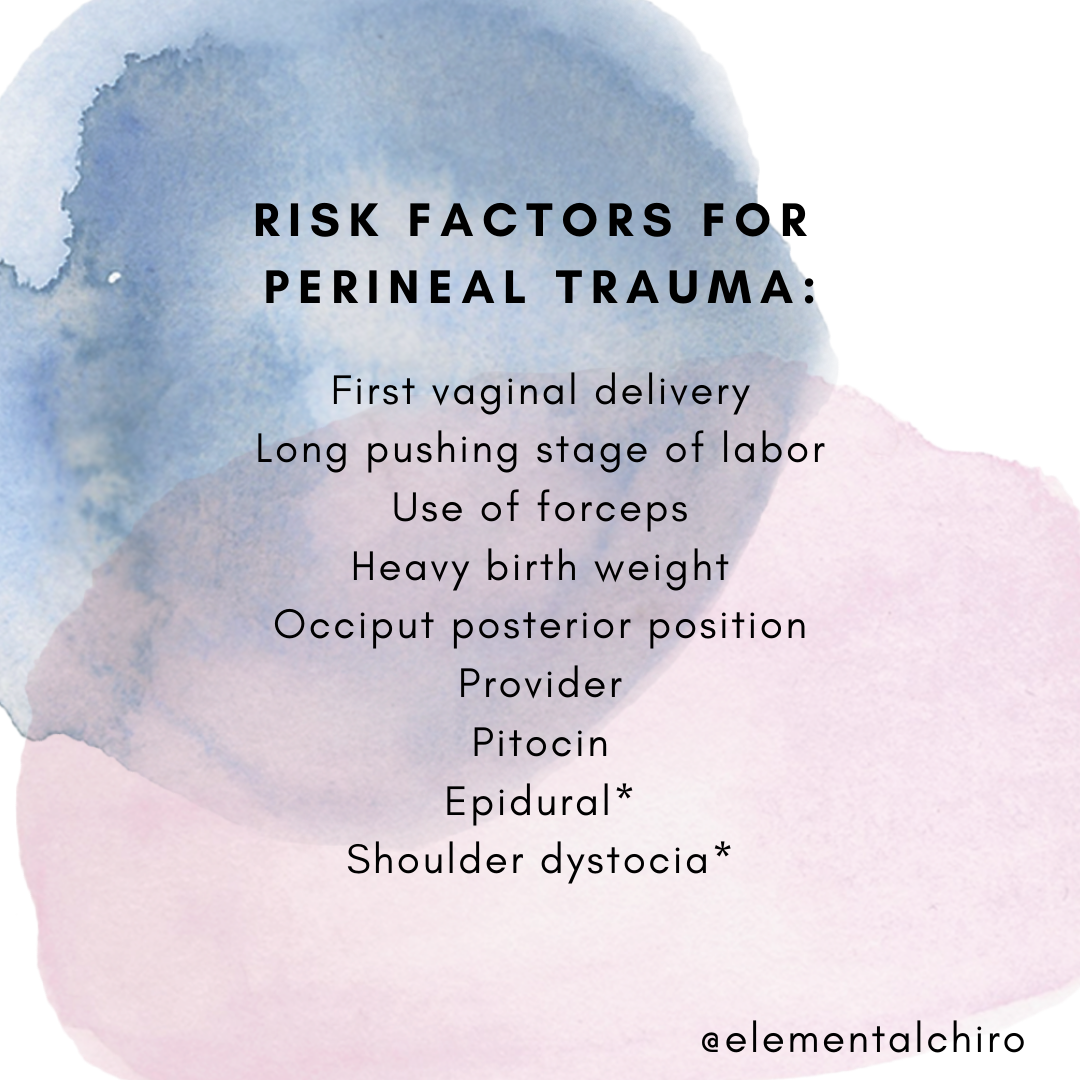

Perineal tearing or lacerations occur as the perineum and the rest of the vulva stretch to allow for the passage of the baby’s head through the vagina. Here’s what we currently know that can increase the likelihood we tear in birth:

First vaginal delivery - people who are having their first vaginal delivery are more likely to tear than if they have previously had a child vaginally. This is also an important note because research has shown that just because a mama tore during an earlier pregnancy does not mean she will tear this time or have the same severity...in fact 95% of mamas with a previous severe tear will not have another.

Long 2nd Stage of Labor - The second stage of labor is often called the pushing phase when the cervix is fully dilated and ends when the baby has arrived. If you find yourself pushing for 2+ hours, this may increase the risk of tearing

Forceps - The use of forceps during delivery increased the risk of third and fourth degree tears

Occiput Posterior Position - This is often called a sunny side up baby and means that the back of the baby’s head that is bony is rubbing on mama’s back. If you suspect an OP baby, check out Spinning Babies for exercises and guidance to help

Heavy birth weight - “Heavier” babies (over 8.8 lbs) may lead to increased risk of tears. However, it’s important to note that late-term ultrasounds are often not reliable in determining body weight (they can actually be off up to 2lbs) and having a “heavy baby” is linked to the next three risks. (6)

Hospital Delivery with OB - Okay, this one is tricky. A few studies have shown that the training an OB receives can actually impact your risk of perineal tears. In fact, one study showed that 31.9% of women with OBs have an intact perineum while 56-61% of women under midwifery care had an intact perineum following birth. Furthermore, 42% of the tears with OBs required suturing while only 35-37% with midwives required repair. (7, 9, 10, 13)

Pitocin: Pitocin is the synthetic version of oxytocin, the hormone the body naturally releases during labor that causes the uterus to contract. During an unmedicated labor, oxytocin increases in response to the baby applying pressure to the cervix and the pelvic floor. Oxytocin works with other hormones to help expel the baby. For more information on the effects of pitocin, oxytocin and the lovely hormones of birth, this is an excellent blog by Dr. Sarah Buckley. (7)

Epidural: This one has mixed risk in research..it’s a chicken or the egg scenario. The reason is that many women who receive epidurals also have more of the other risk factors. All of these inherently increase the risk of perineal tearing on their own so it is unknown if the epidural is truly a risk for increased perineal tears or if it is the “other things” going on like the use of pitocin, provider comfort, or longer labor. (7, 20, 21)

Shoulder Dystocia (when the baby’s shoulder gets stuck inside the pelvis): This is another maybe, maybe not situation. One study highlighted that shoulder dystocia does not increase the risk of tearing but is related to OASIS or obstetrical anal sphincter injury. OASIS often results in anal incontinence, recurring urinary tract infections and pelvic pain. (7, 22)

Is there anything we can do to minimize the risk of perineal tears?

There are some things we have zero control over like first-time vaginal delivery and birth weight. However, there are other things that we may be able to modify to ideally reduce the risk of tears!

Position/Movement: The stereotypical position we see a women giving birth on TV is called the lithotomy position--on her back, feet in straddles, knees up and pushing. Unfortunately the lithotomy position results in the highest rate of tearing. (6,7) There are other birthing positions such as a person being on all-fours or lying on their side, kneeling, standing, squatting or even sitting on a seat (aka the toilet) can actually decrease the risk of tearing! (7, 9, 10)

Avoid “Routine Episiotomy”: Per ACOG, data shows no immediate or long-term maternal benefit of routine episiotomy in perineal laceration severity, pelvic floor dysfunction, or pelvic organ prolapse compared with restrictive use of episiotomy. However, if an instrument-assisted delivery is needed, a medio-lateral episiotomy can prevent OASIS. (1,14).

Perineal Massage and a warm compress: Perineal massage during pregnancy can be beneficial to help mama prepare mentally and physically for labor. Perineal massage during pregnancy does not have a ton of research to reduce tearing; however, many people have stated they feel more confident and comfortable in their body by doing perineal massage. During the second stage of labor, perineal massage and warm compresses by the provider may reduce 3rd and 4th degree tears.

“Rest and Be Thankful”: Sheila Kitzinger identified an additional stage of labor she coined, “Rest and be thankful”. This is the stage of labor when the cervix is fully dilated, the baby has descended but contractions may slow or stop. If left alone, these contractions usually reemerge when the mother and baby are both ready for birth. This helps delay the pushing stage of labor and decreases the time, energy and pressure the mother uses during pushing.

Slow delivery of infant’s head and instructing mother to not push during delivery of head: These often go hand-in-hand during delivery. The TV stereotypical pushing (coached pushing or purple pushing) is when a laboring mother is told “hold your breath and then push as hard as you can for 10 seconds and do this three times in a row.” Mothers that are left alone during birth may experience the fetal ejection reflex where they are not instructed to push during delivery but instead naturally breathe or blow the baby out. (4,5,12,16)

Birth Team and Support Team: This one is important more because of the other risk factors listed above. Will your provider support you while you move during labor or are there restrictions that require you to lie on your back? Is your provider comfortable with applying warm compresses or performing perineal massage? Does the location you are birthing at or your provider restrict the amount of time you can be fully dilated before pushing? What is your provider’s episiotomy rate? If you were to tear, do you still feel supported by your provider? “ How women are cared for during their labour, birth and postnatal period has a direct impact on how they process, understand and rediscover a new sense of self following severe perineal trauma.” (15)

I wish that everything I listed above was a to-do list you could just check off and everything would be perfect. Unfortunately, life and birth are often full of curveballs. The biggest thing I can recommend is that you find a provider and doula that you trust so if the time comes that you need to transfer locations or divert from your birth preferences, you still feel heard and trust those who are supporting you.

If you want prepare your body and pelvic floor for birth, I would be happy to join you on this journey.

Stay Tuned for Part 3: How to heal from a perineal tear postpartum

REFERENCES

Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, O'Connell PR, O'Herlihy C. Anal sphincter disruption at vaginal delivery: is recurrence predictable? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;109:149–152. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00008-3.

Obstetric anal sphincter injury: incidence, risk factors, and management. Dudding TC, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Ann Surg. 2008 Feb; 247(2):224-37.

A multicenter interventional program to reduce the incidence of anal sphincter tears. Hals E, Oian P, Pirhonen T, Gissler M, Hjelle S, Nilsen EB, Severinsen AM, Solsletten C, Hartgill T, Pirhonen J. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Oct; 116(4):901-8.

Decreasing the incidence of anal sphincter tears during delivery. Laine K, Pirhonen T, Rolland R, Pirhonen J. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 May; 111(5):1053-7.

.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29537100

https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6874-14-32

Hoyte, L., Damaser, M.S., Warfield, S.K. et al. Quantity and distribution of levator ani stretch during simulated vaginal childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 199: 198.e1–198.e5

Lien, K.C., Mooney, B., DeLancey, J.O., and Ashton-Miller, J.A. Levator ani muscle stretch induced by simulated vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 103: 31–40

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/episiotomy

SOGC Guideline: Obstetrical Anal Sphincter Injuries (OASIS): Prevention, Recognition, and Repair